Stephen King doesn’t plan his novels in advance. Instead, King sits down and writes whatever springs to mind. He repeats this process every day until he reaches the end of a story.

As one of the most successful writers of his generation, this clearly works for King. Yet King’s endings are notoriously hit and miss. King takes a jab at readers’ criticism of them in the movie It Chapter 2.

King has over 350 million sales to his name, so his readers must value his writing enough to risk disappointment in his final chapters. But you can’t help wonder how much extra value they might receive if King planned to deliver a satisfying conclusion every time.

In the novel writing community, King is known as a “pantser” – a writer who “flies by the seat of their pants”. That is distinct from a “plotter”, who plans their story before writing the first word.

Data scientists can also be pantsers or plotters. But unlike novelists, who consciously decide which camp to join, data scientists tend to drift into “Team Pants” or “Team Plot” without a second thought. Usually the former – much to their detriment.

Most data scientists are conditioned, through their training, to be pantsers. And this is reinforced when they reach the workforce. However, training data scientists to be pantsers is like training funds managers to invest money in lottery tickets. Sometimes you win big, but more likely, it ends in tears.

It’s no surprise around 85% of data science projects never make it into production.

If you want to succeed as a data scientist, you need to plan for it.

Here’s how you can make the shift from pantser to plotter and save your data science career from turning into a horror story.

Are you a Data Science Pantser or Plotter?

"I won’t try to convince you that I’ve never plotted any more than I’d try to convince you that I’ve never told a lie, but I do both as infrequently as possible."

Stephen King

After first learning about data science, I set out to convert those around me to the wonders of data-driven decision making. I spoke to anyone at work who would listen. My goal was to find a project I could use to showcase the value I knew my data skills could bring.

Inspired by my enthusiasm, a senior manager took me up on the offer. She arranged for me to gain access to the main datasets for her business area.

“What would you like me to do with them?” I asked, overlooking the fact that I was the person with data expertise.

“Find something interesting in them,” the manager replied.

And so, for a time at least – until I learned better – I became a data science pantser.

A data science pantser starts with a dataset and plays around with it in the hope of stumbling upon something that will ultimately prove to be of value. A ground-breaking insight or a market-predicting model, perhaps.

By contrast, a data science plotter starts with the end goal in sight and works towards it. They know what insight or model they want to produce and plan accordingly.

The pantser and plotter mindsets correspond to an indefinite and definite viewpoint, as described by entrepreneur Peter Thiel in Zero to One.

People with an indefinite mindset see the future as uncertain and ruled by randomness, so proceed in the hope of stumbling upon the right solution. Meanwhile, those with a definite mindset have a clear view of the future and make concrete plans to work towards it.

Many organisations hire data scientists without a clear idea of what they want them to do. That is, the organisations themselves start from an indefinite viewpoint. What’s more, many data scientists don’t realise the importance of taking the initiative by asking the right questions. No wonder these data scientists become pantsers – whether they like it or not.

But, whereas bestselling novelists can get away with pantsing, it doesn’t work for data scientists.

In the project described above, I went away and threw every analysis technique I knew at the data, and one week later, returned brandishing a slide deck full of “brilliant insights”. As I proudly took the manager through my findings, she seemed unimpressed.

“But I already knew all that,” she said, when I reached the final slide.

A pantser mindset is poison to data science.

Why Pantsing Doesn’t Work in Data Science

“Humans actually do tend to walk in circles when traversing unfamiliar terrain without reliable directional references. If such directional references… are present, people are able to maintain a fairly straight path, even in an environment riddled with obstacles…”

Current Biology, August 20, 2009

Pantsing relies on chance to get you to the best solution. That might happen from time to time – after all, someone has to win the lottery – but you can’t rely on it. It doesn’t work for Stephen King and it doesn’t work for data scientists, either.

People need a clear direction to make sense of the world and progress. Without a clear direction, you will literally walk in circles.

In Zero to One, Peter Thiel gives the example of biotech research, which relies on random chance to discover new drugs – a pantser approach to R&D. Although this research is conducted at scales that do yield results, it is inefficient and subject to diminishing returns. According to Thiel, “the number of new drugs approved per billion dollars spent on R&D has halved every nine years since 1950.”

Data science typically isn’t carried out at the same scale as medical research and doesn’t have the same payoff – either financially or as a benefit to humanity. As a former boss of mine used to say: “we’re not curing cancer here.”

As a result, data scientists don’t have the luxury of being able to deliver multiple failed projects with the promise that a future project will eventually succeed, bringing with it benefits that outweigh the costs of prior failures.

If you deliver multiple failed projects, you’ll probably find yourself looking for a new job. After all, why continue employing someone who isn’t delivering value?

Regardless of your profession, the best way to safeguard your career is by consistently producing valuable outcomes. And as a data scientist, the most effective way to achieve that is by adopting a plotter mindset.

How to Become a Data Science Plotter

“Data is everywhere, but turning it into information isn’t free. It takes focus, effort, consultation and time.”

Seth Godin

Although organisations may take an indefinite viewpoint when hiring data scientists, their motivation is usually the same – to create business value. And data scientists create business value by turning data into information that can be used to make decisions.

Data are raw facts or observations. People refer to data as the new oil, but that description is misleading – oil is a diminishing resource, while data is growing exponentially. We are swimming in data, but in its raw form, that data is meaningless.

Information is data that has been processed to make it meaningful. Still, as Seth Godin pointed out, converting data into information can be expensive, and that information may not even be useful. “Information is only useful if it helps you make a decision.” That is, if it can be used to create business value.

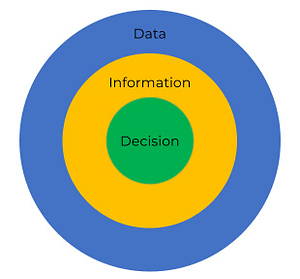

You can think of the process of extracting value from data in terms of three concentric circles:

Data science pantsers start at the outer circle and move inwards, only considering each new circle as they reach it. They hope that when they reach the inner circle, the information they have created will lead to a decision someone actually needs to make.

Universities, MOOCs and Kaggle all instill this “start with the data approach” into data scientists. Kaggle provides participants with a dataset and encourages them to fit a model to the data regardless of why they would actually want to fit it (beyond winning the competition, of course). Universities and MOOCs give students datasets and require them to perform prescribed analysis against them, again with no regard to why.

This approach is effective for teaching data scientists new techniques. Yet, by focussing on the two outer circles, it creates the false impression that the inner circle doesn’t matter. This misconception is rarely corrected in the workforce because both data scientists and their employers fail to realise it exists. You don’t know what you don’t know.

Becoming a data science plotter involves starting at the inner circle and moving out:

- Start by determining the decision you want to make (for example, which of two stocks is the best place for your money);

- Then identify the information you need to make that decision (e.g. the average performance of the two stocks over the past 5 years or projected performance over the next 12 months); and

- Finally, determine the data required to extract that information (e.g. the daily stock price for each stock over the past 5 years).

High value data scientists start with the decision and move out. Knowing the decision you’re heading towards reduces the time needed to deliver value and increases your probability of success.

You are NOT a Lottery Ticket

“You can have agency not just over your own life, but over a small and important part of the world. It begins by rejecting the unjust tyranny of Chance. You are not a lottery ticket.”

Peter Thiel

Pantsing and plotting are two alternative approaches to data science, but only plotting sets you up for success.

Data science plotting may seem like more effort than pantsing – just like plotting a novel is more work that just sitting at a computer and typing. You might need to writing a business case for collecting and storing data you’ve never previously collected. But is it really that much extra effort?

Suppose you adopt a pantser mindset and 90% of your data science projects fail due to lack of direction. That means 90% of your work effectively goes to waste. If you adopt a plotter mindset, on the other hand, and work with a clear goal in mind, you can afford to spend up to 10x the effort on a single project. You can achieve the same or greater business value by directing your efforts where they really matter.

What’s more, adopting a plotter mindset is better for your reputation and for your self-esteem. Failing at 90% of your projects looks bad and will inevitably undermine your self-confidence. Increasing your success rate has the opposite effect.

Stephen King may have become a best-selling writer by surrendering to randomness, but King isn’t a data scientist. Don’t rely on chance to deliver you career success. Develop the habit of planning your projects to lead you there.

In the words of Peter Thiel, “you are not a lottery ticket.” You shouldn’t treat your career as one, either.